Fair and equitable vaccine access is of course needed for the successful transition into a post- pandemic world. However, on a more conceptual level, our success in executing such an equitable transition will also serve as a sort of litmus test for our morality as a global society, and a benchmark for future generations when looking back at this moment in human history.

The fact of the matter is that while politics and economics might care for borders, nationalism, and ideology, biology does not. The virus was and is a threat in all corners of the world – until we are all safe from it, no one is safe from it. This sentiment is echoed by Dr. Angela K. Shen, visiting scientist at the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “Vaccine nationalism only helps the virus propagate. In order for a vaccine to work, you need most of society to be protected — and that protection happens when you get everyone vaccinated. So, you want to roll this out to everyone because, inherently, that’s how you protect everyone collectively,” she states in an interview.

We are already seeing some of the negative consequences of vaccine hoarding – there are some countries that simply don’t have any vaccines at all. These places – also known as vaccine deserts – are the most at-risk of becoming the hotbed for new and more virulent variants of COVID-19.

One such nation is Chad, where just 0.1% of the population have been fully vaccinated. Despite being part of the WHO’s COVAX scheme, they have not received enough vaccines to even cover their frontline health workers.

Even if the vaccines were to arrive – they were promised a batch of Pfizer doses in June – the next challenge becomes storing them. Every vaccine has its own storage requirements, with Pfizer best being kept between -130°F and -76°F, according to the CDC. This is a huge challenge in a country like Chad, where such cooling infrastructure is not very well developed, and it isn’t uncommon for daily temperatures to soar over 100°F.

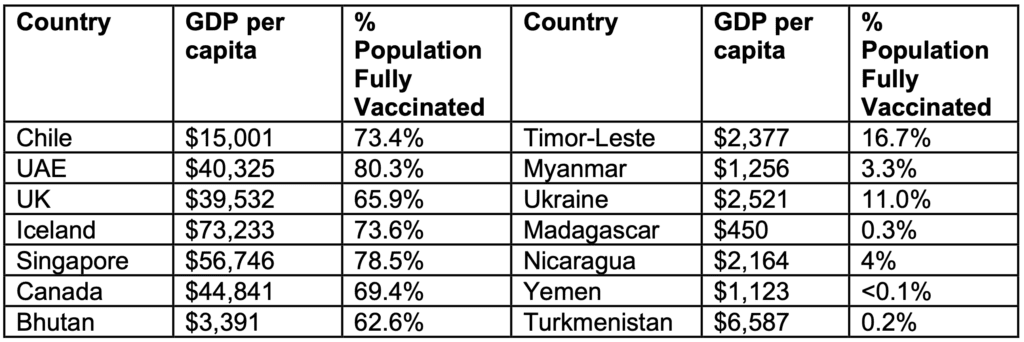

Rolling out vaccines in anything but an equitable way risk creating a segregated two-class global society, one vaccinated society able to enjoy a relatively “normal” life within its metaphorical castle walls, and one society without adequate protection, which can lead to new variants of the virus, but can also lead to exclusion from common activities in our global society.

The way policy is moving in the West, with the introduction of vaccine passports and businesses being allowed to turn away unvaccinated people from jobs, venues, and social spaces, it isn’t a stretch to imagine activities like live music, eating out, getting certain jobs, and international travel could become reserved for the vaccinated class – i.e. those from more economically developed countries. The only way to prevent this dystopian future is to ensure equitable vaccine access for all.